| Search For: |

In Israel, both Jews and non-Jews are free to practice their faiths freely and openly on individual and institutional levels. That contrasts sharply with neighboring Arab states, where intolerance is the norm and the number of non-Muslims is constantly shrinking. The Palestinian Authority’s conduct – including the destruction of Jewish sites and violations of the holiness and neutrality of Christian ones – raises serious doubts whether the Palestinian Authority can be a trusted custodian of sacred sites in the Holy Land – Jewish or Christian.

Freedom House, a non-sectarian organization that monitors civil rights that was founded by Eleanor Roosevelt in 1941, says religious freedom in the world is deteriorating. Moreover, its 2000 survey of religious freedom found that the Middle East was one of the most repressive areas in the world, with one exception – Israel – the only Middle Eastern country ranked among the world’s ‘free’ nations that “enjoys a high degree of religious freedom.”1

Israel extends the fundamental human right of freedom of conscience to members of the majority religion – the Jews (80 percent), and Israel’s minorities (20 percent) – on institutional and personal levels.

Israel guarantees freedom of religion in its Declaration of Independence, and that freedom operates on two levels. In the private sphere there is absolute freedom for all residents – Jews and non-Jews – to be as religious or irreligious as they wish, both at home and in public. In the public sphere, certain aspects of the practices and composition of public bodies and state institutions reflect the fact that Israel was established to serve as a Jewish state by the League of Nations in the Mandate for Palestine document:

“Whereas the Principal Allied Powers have also agreed that the Mandatory should be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 2nd, 1917, by the Government of His Britannic Majesty, and adopted by the said Powers, in favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.”2

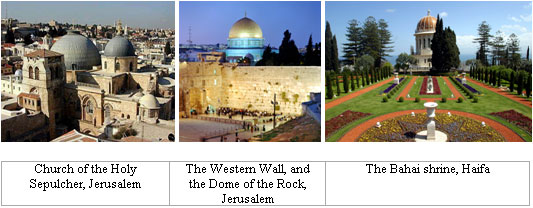

Non-Orthodox streams of Judaism – primarily Reform and Conservative – have established their own institutions in Israel and operate independently, without interference or harassment.3 Israel has never imposed legal restrictions on establishment of non-Orthodox institutions,4 such as places of worship or educational institutions, nor has it prohibited non-Orthodox religious ceremonies or secular substitutes, although certain sensitive public religious sites such as the Western Wall and the Temple Mount require specific rules of behavior for all visitors.5 While Orthodox Jews still monopolize certain state-established and state-supported institutions, such as the Chief Rabbinate, liberalization and pluralization is occurring in many domains. Women and representatives of non-Orthodox movements, for example, now sit on local Jewish religious councils, and female litigators appear in religious courts, where religious divorce cases are settled.6 Change includes state-sponsored or state-supported alternatives:7 For instance, an April 2003 Supreme Court ruling upheld binding rules of behavior at the Western Wall for everyone, provided that an area adjacent to the Wall (Robinson’s Arch) be set aside to accommodate other practices; thus, in August 2004 a plaza was inaugurated at Robinson’s Arch where mixed-gender Reform and Conservative services can be held, and organized all-women prayer groups can congregate.

Beyond laws that guarantee religious freedom, a broad public consensus in Israel supports pluralism and freedom of conscience for the individual and opposes coercion. For instance, a September 2001 public opinion poll of Israeli Jews found that while 57 percent of Jews personally prefer Orthodox weddings for their own families, 65 percent support recognition of non-Orthodox ceremonies.8

While unrestricted abortions concern observant Jews and their leaders, not a single case of arson, threat or murder of physicians performing abortions has been reported in Israel. The ultra-feminists and ultra-Orthodox reached a middle-of-the-road solution that they both can live with.9

Minority faiths,10 Islam, Christianity, the Druze and Bahai sects also enjoy institutional autonomy to serve their members’ needs that is based on a system of recognized religious communities inherited from Ottoman law.11

Although Israel does not have an established state religion as does England, Israel is a Jewish state – that is, one of country’s Basic Laws defines Israel as “a Jewish and democratic state.”12 That designation refers to ‘how Jewish Israel should be as a society.’ The answer is left open to interpretation and issues are hammered out by Israeli Jews – an exceedingly heterogeneous community whose worldviews and practices reflect more than 70 different Diaspora communities and whose degree of religious observance ranges from ultra-secular to ultra-Orthodox.13

Disagreement among Israelis about what it means when Israel is defined as ‘a Jewish state’ is heated, however, issues are settled in battles within the legal and legislative system and at times avid public debate and civic action from lobbying to public demonstrations and appeals to the Supreme Court to rule on the legality of public policy – all without religious warfare and violence.14 This kind of pluralism is not new and has been part of Jewish life in the Diaspora for generations prior to the establishment of Israel.

The following three areas represent matters of conflict or disagreement in the public sphere:

- Sabbath observance by public bodies – from TV transmissions to public transportation and the national airlines, and retail commerce;

- Recognition of non-Orthodox religious functionaries who act as “agents of the state” (to conduct marriages, divorce proceedings, etc.) and apply non-Orthodox criteria to certain personal status issues for Jews;

- Criteria for deciding nationality (who is a Jew from a civil, not religious standpoint) – a necessity in determining eligibility to immigrate under the Law of Return and to register as a Jew in the State’s Population Registry.

Ad hoc local committees of religious and secular Jews who seek peaceful solutions to their conflicting lifestyles are common in Israel. In Zichron Yaakov,15 a community between Tel Aviv and Haifa, a forum was established to initiate dialogue, find common ground and mitigate friction among Zichron’s various communities - veteran winegrowers, religiously-observant townies who came in 1950s, an ultra-Orthodox yeshiva community that came in the 1970s, and a recent flood of largely secular artisans and yuppies who moved to the quaint town in the 1990s and challenged its character.

A desire to live together peaceably leads to creative ways of taking a detour around the religious system to prevent deadlocks.16

In the late 1980s, cinema owners sold tickets to Sabbath cinema performances before the Sabbath, a ploy that led to a change in what is known in Israel as “the religious status quo,” and that ultimately opened all places of entertainment on the Sabbath. More recently, non-Orthodox rabbis who are unauthorized to conduct conversions in Israel began teaching conversion courses in Israel for Russian immigrants who want to convert to Judaism but don’t want to be religiously observant by Orthodox standards. To get around that, non-Orthodox rabbis flew their students to Europe for their conversion ceremonies, which are recognized by the State of Israel as Diaspora conversions under the “religious status quo” pertaining to Jewish immigrants. In March 2005, the Israel Supreme Court rule that that Israeli residents traveling overseas solely for the purpose of undergoing the formal conversion ceremony (dubbed “leaping converts”) was legal and such converts should be recognized by the State.17

The “status quo” concept is a modus operandi agreed upon by religious and non-religious Jews that places controversial or insoluble issues on hold so that they do not cause constant friction. The “status quo” covers a host of unsettled issues, from military exemptions on religious grounds and Sabbath observance in the public sphere to the interpretation of who is a Jew.

The “status quo” has hardly been ‘set in stone’; it is dynamic and changes as crises arise and reality rears its head. Attempts to paint Israel as increasingly religious or intolerant and theocratic are unwarranted. Consider some of the changes Israel has made in almost six decades since the establishment of Israel in 1948. Ultra-Orthodox residents rioted in Jerusalem in the late 1950s when a public co-ed swimming pool was opened. Today, discos and pubs are packed on Friday nights in Jerusalem, and cheeseburgers, by definition non-kosher, are sold in the heart of the city.18

Some of the arrangements – such as permitting the sale of pork but limiting its public display – may seem strange to American observers, but they faithfully reflect the quirks of Jewish community life and Jewish values. The modus operandi hammered out – through the courts and legislation, public debate and public protest, ad-hoc committees and detour mechanisms – reflect Israeli society’s resilience and its ability to find creative win-win solutions that will preserve Jewish unity, despite internal tensions. More to the point, these social practices underscore Israel’s overriding tolerance as a society, despite Israelis’ public and often fiery debates. Ultimately, these mechanisms, based more on consensus building than raw power plays, have allowed Israel to maintain a strong common denominator and sense of commonality.19

It is important to realize that in many cases, religious debate ignites strong emotions, and sometimes violence, in a pluralistic society. In Israel, there has not been religious warfare or serious violence instigated by religion. That is partly because of a host of public-spirited frameworks that proactively reduce tension and prevent polarization by nurturing dialogue, breaking down stereotypes and encouraging empathy and respect for the ‘Other.’20

Since 1990, Israeli society has shown an admirable degree of willingness and flexibility in solving religious problems in the wake of the influx of one million immigrants from the former Soviet Union and Ethiopia. The solutions were based on ‘live-and-let-live’ philosophy.

Such accommodation contrasts sharply with Palestinian society. While the number of Christians in Palestinian-Muslim society has shrunk from 15 percent in 1950 to 2 percent in 2002, Israel has absorbed tens of thousands of non-Jews among the one million immigrants that have come from the former Soviet Union since 1990. The immigrants – mostly non-observant Jews, a significant number with non-Jewish spouses – have made new demands on the system and have sparked social tensions over cultural norms.

Still, in scores of Israeli cities and towns, observant and secular, veterans and newcomers work together to address the challenges that could otherwise tear communities asunder. On local and national levels, ways are being sought to accommodate the needs of non-Jews and Jews who don’t meet the Orthodox criteria of ‘Who is a Jew,’ without compromising Orthodox standards that govern state-established religious institutions.

One of the most important solutions was agreement by all, including the Orthodox establishment, to establish non-sectarian cemeteries alongside strictly religious ones. That accommodation allows non-Orthodox or alternative funerals and other burial choices for those who are not Jewish by Jewish law (Halacha); for both spouses from mixed marriages; and for Jews who prefer non-Orthodox or non-religious arrangements. Similarly, special arrangements were made that allow non-Jewish soldiers to use the New Testament at swearing-in ceremonies. In many development towns, joint committees of tradition-bound longtime Jewish residents and secular newcomers – primarily Jews from Russia – have made arrangements that reduce inter-ethnic tensions.

The growing dialogue among Jews and co-religionists of other opinions, the tolerance Israelis exhibit toward other religious minorities and the Jewish state’s record of respect for the places of worship and holy sites of other faiths, contrasts starkly with the milieu of intolerance and absence of religious freedoms among Israel’s Arab neighbors.21

Reports describe treatment of non-Muslims in Arab lands that range from relegation to second-class-citizen status to stringent restrictions on religious expression in the public domain, from mild harassment to horrific acts of violence designed to drive them out of Muslim lands.22

One of the worst offenders is Saudi Arabia, which “prohibits any form of public non-Muslim religious activities; non-Muslim worshippers risk arrest, imprisonment, lashing, deportation, and sometimes torture for engaging in religious activity” (including prayer groups in private houses that have the misfortune to attract official attention). The official religion is an extreme form of Islam that takes Islamic Sharia law literally – and sanctions judicial amputation for theft including cross-amputations of an arm and a leg.23,24

Because of hostility and discrimination, the number of Christians in the Middle East has dropped drastically as more and more emigrate to the West. Under Jordanian control prior to the Six-Day War, the number of Christians in Jerusalem shrank by 61 percent between 1948 and 1967, due to a combination of demographics and growing hostility toward non-Muslims. Thousands more emigrated to the West after the Palestinian Authority was established. Christians are fast becoming an endangered species in Islamic countries, just as the Jews were a minority in Arab lands since 1948. More recently, areas transferred to the Palestinian Authority have seen a loss of their Jewish populations.

Israelis who venture into Palestinian-controlled areas – be they secular or religious Jews - have been brutally murdered, while Arab citizens in Israel and Palestinian Arabs who live in the Territories and have Israeli work permits continue to frequent Jewish cities unmolested.25

In a series of signed agreements since Oslo (1993), the Palestinian Authority promised to protect and grant free access to all religious sites under their jurisdiction, but has systematically broken its commitments.

Palestinian political and religious leaders systematically use the media, the schools and the pulpit to disseminate false, slanderous and inflammatory propaganda that claims Jews and Judaism have no historic roots in the Land of Israel. They deliberately destroy archaeological evidence, even on the Temple Mount, Judaism’s holiest site. Jewish religious sites in PA-controlled areas also have been ransacked and destroyed.26,27

In the “Oslo II” Accord (28 September 1995) the PA signed and guaranteed protection and free access to Joseph’s Tomb (described in Joshua 24:32) on the outskirts of Nablus and to the Shalom al-Yisrael (“Peace on Israel”) synagogue built in Jericho in 700 AD – both in areas slated for Palestinian control.28 During the first days of the Terror War, a besieged IDF unit guarding a small yeshiva at Joseph’s Tomb withdrew after Palestinian authorities promised to protect the holy site, but the Tomb was immediately torched and the dome painted green (the color of Islam).29 Jews have been unable to visit the two sites ever since, due to the risk to their lives. In February 2003, it was learned that Palestinians had reduced the cenotaph inside the shrine to rubble.30 The Jerusalem Waqf (the Muslim trust that holds custodianship over Islamic holy places in Jerusalem) barred non-Muslims from visiting the Temple Mount – the third holiest shrine in Islam, and the holiest site in Judaism, for more than 2½ years immediately after the outbreak of the Terror War (September 2000 – August 2003). Visits were only reinstated after Israeli police began escorting groups of Christian and Jews around the site in June 2003, thus ‘convincing’ the Waqf to begin honoring its commitment of free access to the Temple Mount area.

Muslim religious leaders who use their pulpits with impunity to incite and breed hatred are supported and subsidized by the Palestinian Authority, which neither reins in such employees nor opposes such instances of mob rule. By its own conduct, the Palestinian Authority raises fundamental questions about whether Palestinians can be trusted to protect non-Muslim holy sites – Jewish or Christian.

Muslim religious leaders have compromised the purity of their faith by cynically using fatwas – Islamic religious rulings – as political instruments to sanction terrorism against Jews. Palestinians and their supporters fail even to respect the holiness of their own religion’s holy sites and objects, as evidenced by the suicide belts Palestinian terrorists hid in a mosque in Israel in February 2003.31

In Palestinian-controlled areas, the Palestinian Authority has often acted like a bull in a china shop, disregarding the delicate arrangements controlling religious sites that for centuries prevented friction among Christian sects.32 In addition, at the beginning of the Terror War, for over a year, Muslim Palestinians combatants forcibly turned the strategically located Christian Arab conclave Beit Jalla – a middle class village studded with churches and monasteries and known for its moderation – into a platform for gunners’ nests in order to fire into Gilo, a Jewish neighborhood across the valley. The neutrality and holiness of monasteries and churches have been cynically compromised. The worst violation was the turning of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem into a ‘sanctuary’ at gunpoint; in April 2002, over 100 Palestinian gunmen forced their way into the Church which marks the birthplace of Jesus, to avoid being apprehended by Israeli forces and to ‘create international pressure on Israel.’ According to the State Department, in the course of the five-week standoff, the gunmen caused “considerable material damage” to the Church of the Nativity.33

Christian Arabs are in a very delicate situation: They are Palestinians by ‘nationality,’ but a tiny religious minority within Palestinian society. Their situation has worsened since the launch of the Terror War, which is an almost exclusively Muslim ‘enterprise’ with a growing religious dimension, while suicide bombers are an exclusively Muslim phenomenon.

Christian Arabs under the PA are increasingly subject to the kind of intolerance common under other Arab regimes, including religious persecution of individuals and political oppression of religious communities.34 According to the State Department’s 2005 annual assessment of religious freedom, one of the worst forms of intimidation was a number of cases where criminal gangs using forged land documents seized lands belonging to Christians in Bethlehem in collusion with Palestinian Authority security forces and judicial officials.35 In fact, these incidents are only the tip of the iceberg. The actual plight of the Palestinian Christian community is for the most part overlooked and underplayed, the State Department reports. A ground-breaking study by Justus Reid Weiner “Human Rights of Christians in Palestinian Society” published in 2005 sheds light on realities.36

Weiner says that Christians under Palestinian Authority governance, as tiny minority, lack the clout, numerically and politically, to protect its members and the community’s wellbeing. Since 2000, they have been further marginalized by a number of factors: the Islamization of the Israeli-Arab conflict and different demographics/economic status and divergent core values from their Muslim neighbors. Their ‘Otherness’ has been exacerbated by the Muslim majority’s embracement of a radical Islamic shahid culture and hostility towards all Christians ‘fueled’ by the global war on terrorism.

Weiner found that “the persecution of Palestinians Christian is diverse and widespread, through not commonly acknowledges.” The 50-page study documents institutional discrimination due to the role of Sharia law in the PA judicial system; radical Muslim religious instruction and incitement in the schools; widespread discrimination in the workplace – both the civil service and other sectors; boycott of Christian businesses and extortion on religious grounds; “pervasive” abuse of Christian property and vandalism; “widespread” sexual harassment of Christian girls37 and imposition of Islamic dress codes; vitriolic incitement in mosques and the media against Christians as unpatriotic – ‘Israeli collaborators’ or ‘Islam’s enemies’; and persecution of converts to Christianity. There is largely a conspiracy of silence surrounding these phenomena because Christian Arabs are afraid to speak out or even report abuses – both out of fear that this would worsen their already precarious situation and out of fear exposure would hurt the Palestinian cause. Others are in a state of denial in the war to survive or too intimidated38 to protest, he says. Almost all the depositions and interviews were conducted on condition of anonymously. The study concludes:

“Not only is the Palestinian Christian community facing an existential threat [E.H., due to heightened emigration since establishment of the Palestinian Authority and gerrymandering that turned Bethlehem into a Muslim-dominated town], but even more significantly, their status as a persecuted minority is ignored as international attention focuses on terrorism and inchoate peace plans rather than on present human rights needs.”

Lack of religious freedom cannot be viewed in a vacuum or as a problematic issue separate from democratization, or as ‘irrelevant’ to the war on terrorism – not when religion is systematically exploited to inflame the Arab-Israeli conflict and fuel hatred of America and the West.39

The institution of religious freedoms in Arab countries and control of extremist clerics must be part of the battle against terrorism, because of the key role religion plays in fueling hatred and legitimizing terrorism. It is not enough to eradicate terrorist groups and their international support networks, stressed Amy Hawthorne a Soref fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, in testimony before the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom in November 2001. The war on terrorism must also “advance a positive vision for the peoples of the Middle East that [can] provide an alternative to terrorists’ destructive ideology. This will require the United States to shed its reluctance to engage local leaders on the highly sensitive issues of political reform, rule of law, and the spread of democratic values. The widening of religious freedom must be a cornerstone of this effort.”40

-

Israel is the only country in the Middle East that allows genuine freedom of conscience and protects sacred sites of all faiths.

-

Non-Jews in Israel – indigenous minorities and new immigrants – practice their religions freely and openly, as individuals and on institutional levels.

-

Disagreements among Jews over Israel’s character as a “Jewish and democratic state” are settled democratically, without religious warfare or violence.

-

Religious controversy is often defused via compromise arrangements and detour mechanisms rather than naked power plays. Over the past three decades, Israel has become more inclusive, tolerant and pluralistic in matters of religion.

-

In contrast, in all too many neighboring Arab countries, extremist streams of Islam and growing intolerance for “the Other” – Muslim or non-Muslim – have become dominant.

-

The Palestinian Authority’s reckless behavior and utter failure to uphold religious freedom or to respect and protect members of other faiths and their institutions – Jewish or Christian – make the PA no different than other intolerant Arab regimes.

-

Christian Palestinians have become a persecuted minority in Palestinian society under Palestinian self-rule. Many have fled to the west, most others are afraid to speak up.

-

The Palestinians are not worthy of stewardship over the holy sites of others.

http://www.freedomhouse.org/religion/pdfdocs/rfiwmap.pdf. (11132)

2 See “Mandate for Palestine” document at:

http://middleeastfacts.org/content/UN-Documents/Mandate-for-Palestine.htm. (10448)

3 Statistics source, the American Reform Movement. For information on their operation, see the Israel Movement for Progressive Judaism (Reform) website, at:

http://www.reform.org.il/English/default.htm and the Masorati (Conservative) Movement in Israel, at:

http://www.masorti.org/ The liberal movements advertise in the media to attract non-observant Israelis to study groups and synagogues. Most congregants, however, are Jews from English-speaking countries, and since the 1990s also Russian immigrants.

4 For an academic study of Reform Judaism in Israel, see Ephraim Tabory, “Reform Judaism in Israel: Progress and Prospects,” the American Jewish Committee, (No Date), at:

http://www.ajc.org/site/apps/nl/content3.asp?c=ijITI2PHKoG&b=840313&ct=1051411. (11663) For a look at Conservative Judaism in Israel, see Harvey Meirovich, “The Shaping of Masorati Judaism in Israel,” the American Jewish Committee, (No Date) at:

http://www.ajc.org/atf/cf/%7B42D75369-D582-4380-8395-D25925B85EAF%7D/ShapingMasortiJudaismIsrael.pdf. (11664)

5 For more insights on how freedom of religion operates in a complex reality, see Ruth Lapidoth and Ora Ahimeir, “Freedom of Religion in Jerusalem” 1999, Research Series No. 85, Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies.

6 For a close look at broadening representation on religious councils, for example, see:

http://www.adl.org/israel/jerusalemjournal/JerusalemJournal-990126-2.asp. (11141)

7 This includes, for instance, establishment of alternative cemeteries and attempts to reach a consensus on a civil marriage option – both discussed elsewhere in the chapter.

8 For this and more results on tolerant public attitudes, see Yael Mayer, “Israelis Support Progressive Views on Religion and State,” Israel Religious Action Center, September 25, 2001, at:

http://www.irac.org/article_e.asp?artid=478. (11665)

9 Hospitals perform legal abortions on the recommendation of hospital abolition committee comprised of health professionals, but eligibility is very broad, although stopping short of ‘abortion on demand.’

10 Yishai Eldar, “Microcosm and Multiple Minorities: The Christian Communities in Israel,” Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, March 30, 2004 at:

http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/Facts%20About%20Israel/People/Focus%20on%20Israel%20-%20The%20Christian%20Communities%20of%20Isr. (11666) Ben-Dor, “The Druze Minority in Israel in the Mid-1990s,” Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, June 1, 1995, at:

http://www.jcpa.org/jl/hit06.htm. (11143) Robin Twite, “Interfaith Activity in Israel,” Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, November 1, 1999, at:

http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/MFAArchive/1990_1999/1999/11/Interfaith%20Activity%20in%20Israel. (11144)

11 On the operation of Muslim and Druze religious courts in Israel, see:

http://reference.allrefer.com/country-guide-study/israel/israel103.html. (11145)

12 For an essay by the president of the Israeli Supreme Court on how Israel integrates being both a democratic and Jewish state, see Aharon Barak, “Some people say a state that is both Jewish and Democratic is an oxymoron, but the values can work together,” Forward, August 23, 2002, at:

http://www.myjewishlearning.com/history_community/Israel/Israeli_Politics/IsraeliSupremeCourt/DemocraticJewish.htm. (11146) For a conversation with Supreme Court Justice Menachem Elon, an observant Jew, see: “We are bound to anchor decisions in the values of a Jewish and democratic state,” in Justice, the periodical of the International Association of Jewish Lawyers and Jurists, June, 1998, pp. 10-15 , at:

http://www.intjewishlawyers.org/pdf/Justice%20-%20%2017.pdf. (11147)

13 For an ‘inside’ picture of various Jewish lifestyles from ultra-Orthodox to New Age-like mysticism and ultra-secular, see Part III “Widening Fault Lines Between Jews and Jews,” in Donna Rosenthal, The Israelis, Ordinary People in an Extraordinary Land, Free Press, 2003. The other profiles of the mosaic of Israeli society – various ethnic communities, minority groups, the gay community and others, are equally revealing.

14 For an historic overview of relations between religion and state in Israel from 1948 to the present, see “The Conversion Crisis - The Current Debate on Religion, State and Conversion in Israel,” Anti-Defamation League Jerusalem Journal, 2001, at:

http://www.adl.org/israel/conversion/Conversion_print.asp. (11668)

15 For examples on how living together is carried out in practice in one Israeli town – Zichron Yaakov - see Dr. Victor J. Friedman, Engaging ‘Fuzzy’ Conflicts: The Role of Action Evaluation, August, 1998, Ruppin Institute at:

http://www.aepro.org/inprint/conference/friedman.html. (11152)

16 On the concept of “detouring a bottlenecked system” see Sam N. Lehman-Wilzig, “Religion and State – Holy Wars,” in Wildfire – Grassroots Revolutions in Israel in the Post-Socialist Era (New York: SUNY Press, 1992), pp. 115-28.

17 That is, for the purposes of establishing nationality in the Population Registry and residency issues such as entitlement to immigrant status, not for Orthodox marriage.

18 There is not only protest on religious grounds, but also secular Jews who attack the practice on ethical grounds (unfair competition, forcing Jewish shop owners and employees to work on the Sabbath out of economic necessity) and lament the loss of Israel’s ‘special Sabbath milieu’ sacrificed in the name of convenience and consumerism. See Matthew Gutman, “Unity Is Price as Malls Open on Shabbat,” Forward, December 13, 2002, at:

http://www.forward.com/issues/2002/02.12.13/news8.html, (11669) and Hillel Halkin, “You don't have to be Orthodox to cherish the Sabbath,” Jewish World Review, December 13, 2002, at:

http://www.jewishworldreview.com/hillel/halkin121303.asp. (11670)

19 Daniel J. Elazar, “Religion in Israel: A consensus for Jewish Tradition,” Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, 1996 at:

http://www.jcpa.org/dje/articles2/relinisr-consensus.htm, (11154) and “Orthodox and Non-Orthodox Judaism: How to Square the Circle,” 1997, at:

http://www.jcpa.org/dje/articles2/orth-nonorth.htm. (11156)

20 For example, see the work of two NGO reconciliation frameworks: Gesher (Bridge) at:

http://www.gesher.co.il/english/ and Common Denominator at:

http://www.commondenominator.jp/. For a glimpse at the graphics of a media campaign – Tzav Pius (‘Reconciliation - Order of the Day’) – a project of the Avi-Chai Foundation designed to break down stereotypes and encourage dialogues between religious and non-religious Jews in forging the character of a Jewish state, see:

http://www.tzavpius.org.il/eng/whoRw.asp?catID=7.

21 For studies on images of other religions in Israeli, Palestinian, Syrian, and Saudi Arabian schoolbooks, see the reports of the Center for Monitoring the Impact of Peace at:

http://www.edume.org/reports/report1.htm For a brief summary of differences between Israeli and PA textbooks, see:

http://www.edume.org/news/march02.htm. (11671)

22 On the record of Arab states in failing to foster tolerance or protect religious freedom, see for example, Habib C. Malik, “Christians in the Land Called Holy,” First Things, January 1999,

http://www.firstthings.com/ftissues/ft9901/opinion/malik.html. (11161) “Religious Persecution in the Middle East” – testimony of Professor Walid Phares before the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, May 1997, at:

http://mypage.bluewin.ch/ameland/LectureE3.html. (11162) “Christians in the Middle East,” The Peace Encyclopedia at:

http://www.yahoodi.com/peace/christians.html. (11672) “State Department Blasted for Lauding PA’s ‘religious tolerance,’ October 11, 2002”, at:

http://www.freedomhouse.org/religion/country/Israel & occupied/State blasted.htm. (11673)

23“2005 Annual Report on International Religious Freedom: Saudi Arabia,” Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor U.S. Department of State, at:

http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2005/51609.htm. (11674) For descriptions of conditions for Christians, see Nina Shia, “Kingdom’s Religious Wrongs - The religious tyranny in Saudi Arabia is not just Saudis’ business,” National Review, April 25, 2005, at:

http://www.nationalreview.com/comment/shea200504250752.asp. (11675)

24 “Amnesty demands Saudi probe,” BBC, March 17, 2000, at:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/681597.stm. (11166) Testimony on religious persecution in Saudi Arabia before the U.S. House of Representatives, Subcommittee on International Operations and Human Rights, March-April 2000, at:

http://www.freedomhouse.org/religion/publications/newsletters/2000/March-April/newsletter_2000-mar04.htm. (11167)

25One telling example is the circumstances of the murder of Mottie Dayan and Etgar Zeitouny, at:

http://www.israel-mfa.gov.il/mfa/go.asp?MFAH0j7m0. (11676)

26 “Palestinian Denial of Jewish Holy Sites, assaults on Christian and Jewish holy sites by the Palestinian Authority. Jerusalem Fund of Aish Hatorah, (No Date), at:

http://www.aish.com/Israel/articles/Palestinian_Denial_of_Religious_Freedom_p.asp. (11662)

27 Mark Ami-el, “Destruction of the Temple Mount Antiquities,” Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, August 2002, at:

http://www.jcpa.org/jl/vp483.htm. (11567)

28 Oslo II - See Annex I, Article V and Appendix 4 – Jewish Holy Sites at:

http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/Peace+Process/Guide+to+the+Peace+Process/THE+ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN+INTERIM+AGREEMENT+-+Annex+I.htm#article5. (11661)

29 Lyse Doucet “Jewish Shrine Ransacked,” BBC, October 7, 2000, at:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/961710.stm. (11642)

30 “Arab vandals desecrate Joseph's Tomb - Gravestone of biblical patriarch ruined despite Palestinian pledge,” WorldNet Daily, February 25, 2003, at:

http://worldnetdaily.com/news/article.asp?ARTICLE_ID=31203. (11657)

31 “Israel warns of Iraq war 'earthquake' – Bomb-belt Found,” BBC News, February 7, 2003, at:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/2736283.stm. (11176)

32 For instance, in January 2000, Palestinian police evicted five "White Russian" monks from their 19th-century monastery in the West Bank town of Jericho, handing the property over to the Moscow Patriarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church. Cited in Lenny Ben-David, “Denial of Religious Rights by the Palestinian Authority” at:

http://www.honestreporting.com/articles/reports/Denial_of_Religious_Rights_by_the_Palestinian_Authority.asp. (11175)

33 Details were extracted from the State Department’s 2004 and 2005 reports and the Weiner study. See “Israel and the Occupied Territories” in International Religious Freedom Report for 2004 and 2005, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, at:

http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/. (11658) and Justus Reid Weiner, “Human Rights of Christians in Palestinian Society,” Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, 2005, at:

http://www.jcpa.org/text/Christian-Persecution-Weiner.pdf. (11659) To end the affair it was agreed that the gunmen holding up in the Church would be ensured safe passage out, but would be ‘exiled’ to Europe on British planes via Cyprus.

34 Lenny Ben-David, “Denial of Religious Rights by the Palestinian Authority” Op. cit.

35 See “Israel and the occupied territories” in the 2005 International Religious Freedom Report, Op. cit.

36 Justus Reid Weiner, “Human Rights of Christians in Palestinian Society,” Op. cit.

37 Christian informants told Weiner that their communities are unable to protect their women because the ‘mutual deterrent’ mechanism of violent reprisal for any violation of ‘women’s honor’ fails to work for Christians due to their numerical inferiority, particularly under present conditions of lawlessness where the only rule is vigilante rule.

38 Informants reported being told “After Saturday, comes Sunday” (alluding that first Palestinian Muslims would deal with the Jews, then with Christians.)

39 “Role of Religion” in Israel Science and Technology Homepage overview of the Arab-Israeli conflict, (No Date), at:

http://www.science.co.il/Arab-Israeli-conflict-2.asp. (11177)

40 Amy W. Hawthorne, a Soref fellow of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy addressing the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom on November 27, 2001, “Promoting Religious Freedom in the Arab World, Post–September 11,” at:

http://washingtoninstitute.org/templateC05.php?CID=1464. (11660)

This document uses extensive links via the Internet. If you experience a broken link, please note the 5 digit number (xxxxx) at the end of the URL and use it as a Keyword in the Search Box at www.MEfacts.com