2. The “Mandate for Palestine” Document

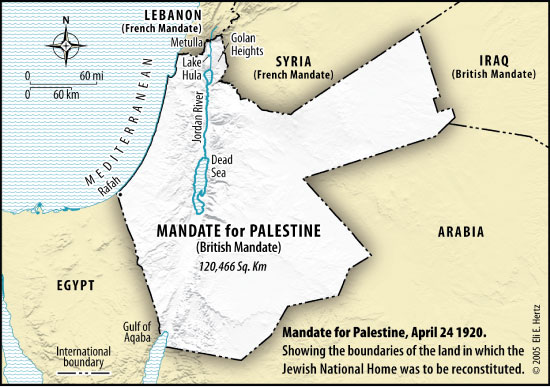

1920 - Original territory assigned to the Jewish National Home

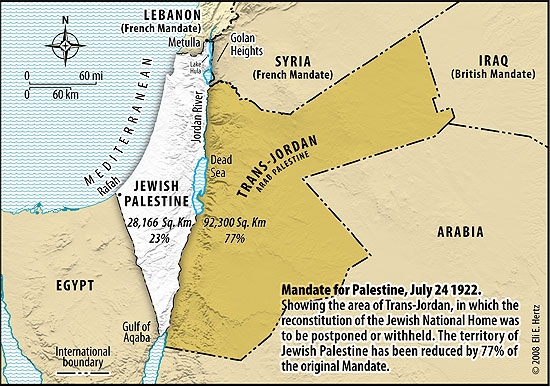

1922 - Final territory assigned to the Jewish National Home

The ICJ, in noting it would briefly analyze “the status of the territory concerned,” and the “Historical background,” fails to cite the true and relevant content of the historical document, the “Mandate for Palestine.”1

The “Mandate for Palestine” [E.H., the Court refers to as “Mandate”] laid down the Jewish right to settle anywhere in western Palestine, the area between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, an entitlement unaltered in international law and valid to this day.

The legally binding Mandate for Palestine document, was conferred on April 24 1920, at the San Remo Conference and its terms outlined in the Treaty of Sevres on August 10 1920. The Mandate’s terms were finalized on July 24 1922, and became operational in 1923.

In paragraphs 68 and 69 of the opinion, ICJ states it will first “determine whether or not the construction of that wall breaches international law.” The opinion quotes hundreds of documents as relevant to the case at hand, but only a few misleading paragraphs are devoted to the “Mandate.” Moreover, when it comes to discussing the significance of the ‘founding document’ regarding the status of the territory in question – situated between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, including the State of Israel, the West Bank and Gaza – the ICJ devotes a mere 237 murky words to nearly 30 years of history when Great Britain ruled the land it called Palestine.

All the more remarkable, the ICJ thinks that the “Mandate for Palestine” was the founding document for Arab Palestinian self-determination!

The ICJ’s faulty reading of the “Mandate.”

“Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire. At the end of the First World War, a class ‘A’ Mandate for Palestine was entrusted to Great Britain by the League of Nations, pursuant to paragraph 4 of Article 22 of the Covenant, which provided that: ‘Certain communities, formerly belonging to the Turkish Empire, have reached a stage of development where their existence as independent nations can be provisionally recognized, subject to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by a Mandatory until such time as they are able to stand alone.’”2

The judges choose to speak of “Palestine” in lieu of the actual wording of the historic document that established the Mandate for Palestine – “territory of Palestine.”3 The latter would demonstrate that “Palestine” is a geographic designation, and not a polity. In fact, Palestine has never been an independent state belonging to any people, nor did a Palestinian people, distinct from other Arabs, appear during 1,300 years of Muslim hegemony in Palestine under Arab and Ottoman rule. Local Arabs during that rule were actually considered part of and subject to the authority of Greater Syria (Suriyya al-Kubra).

The ICJ, throughout its lengthy opinion, chooses to speak incessantly of “Palestinians” and “Palestine” as an Arab entity, failing to define these two terms and making no clarification as to the nature of the “Mandate for Palestine.”

Palestine is a geographical area, not a nationality.

Below is a copy of the document as filed at the British National Archive describing the delineation of the geographical area called Palestine:

PALESTINE

INTRODUCTORY.

POSITION, ETC.

Palestine lies on the western edge of the continent of Asia between Latitude 30° N. and 33° N., Longitude 34° 30’ E. and 35° 30’ E.

On the North it is bounded by the French Mandated Territories of Syria and Lebanon, on the East by Syria and Trans-Jordan, on the South-west by the Egyptian province of Sinai, on the South-east by the Gulf of Aqaba and on the West by the Mediterranean. The frontier with Syria was laid down by the Anglo-French Convention of the 23rd December, 1920, and its delimitation was ratified in 1923. Briefly stated, the boundaries are as follows:

North. – From Ras en Naqura on the Mediterranean eastwards to a point west of Qadas, thence in a northerly direction to Metulla, thence east to a point west of Banias.

East. – From Banias in a southerly direction east of Lake Hula to Jisr Banat Ya’pub, thence along a line east of the Jordan and the Lake of Tiberias and on to El Hamme station on the Samakh-Deraa railway line, thence along the centre of the river Yarmuq to its confluence with the Jordan, thence along the centres of the Jordan, the Dead Sea and the Wadi Araba to a point on the Gulf of Aqaba two miles west of the town of Aqaba, thence along the shore of the Gulf of Aqaba to Ras Jaba.

South. – From Ras Jaba in a generally north-westerly direction to the junction of the Neki-Aqaba and Gaza Aqaba Roads, thence to a point west-north-west of Ain Maghara and thence to a point on the Mediterranean coast north-west of Rafa.

West. – The Mediterranean Sea.

Like a mantra, Arabs, the UN, its organs and now the International Court of Justice have claimed repeatedly that the Palestinians are a native people – so much so that almost everyone takes it for granted. The problem is that a stateless Palestinian people is a fabrication. The word ‘Palestine’ is not even Arabic.4

In a report by His Majesty’s Government in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to the Council of the League of Nations on the administration of Palestine and Trans-Jordan for the year 1938, the British made it clear: Palestine is not a State but is the name of a geographical area.5

The ICJ Bench creates the impression that the League of Nations was speaking of a nascent state or national grouping – the Palestinians who were one of the “communities” mentioned in Article 22 of the League of Nations. Nothing could be farther from the truth. The Mandate for Palestine was a Mandate for Jewish self-determination.

It appears that the Court ignored the content of this most significant legally-binding document regarding the status of the Territories.

Paragraph 1 of Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations reads:

“To those colonies and territories which as a consequence of the late war have ceased to be under the sovereignty of the States which formerly governed them and which are inhabited by peoples not yet able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world, there should be applied the principle that the well-being and development of such peoples form a sacred trust of civilization and that securities for the performance of this trust should be embodied in this Covenant.”6

The Palestinian [British] Royal Commission Report of July 1937 addresses Arab claims that the creation of the Jewish National Home as directed by the Mandate for Palestine violated Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, arguing that they are the communities mentioned in paragraph 4:

“As to the claim, argued before us by Arab witnesses, that the Palestine Mandate violates Article 22 of the Covenant because it is not in accordance with paragraph 4 thereof, we would point out (a) that the provisional recognition of ‘certain communities formerly belonging to the Turkish Empire’ as independent nations is permissive; the words are ‘can be provisionally recognised’, not ‘will’ or ‘shall’: (b) that the penultimate paragraph of Article 22 prescribes that the degree of authority to be exercised by the Mandatory shall be defined, at need, by the Council of the League: (c) that the acceptance by the Allied Powers and the United States of the policy of the Balfour Declaration made it clear from the beginning that Palestine would have to be treated differently from Syria and Iraq, and that this difference of treatment was confirmed by the Supreme Council in the Treaty of Sevres and by the Council of the League in sanctioning the Mandate.

“This particular question is of less practical importance than it might seem to be. For Article 2 of the Mandate requires ‘the development of self-governing institutions’; and, read in the light of the general intention of the Mandate System (of which something will be said presently), this requirement implies, in our judgment, the ultimate establishment of independence.

“(3) The field [Territory] in which the Jewish National Home was to be established was understood, at the time of the Balfour Declaration, to be the whole of historic Palestine, and the Zionists were seriously disappointed when Trans-Jordan was cut away from that field [Territory] under Article 25.” [E.H., That excluded 77 percent of historic Palestine – the territory east of the Jordan River, what became later Trans-Jordan.]7

The “inhabitants” of the territory for whom the Mandate for Palestine was created, who according to the Mandate were “not yet able” to govern themselves and for whom self-determination was a “sacred trust,” were not Palestinians, or even Arabs. The Mandate for Palestine was created by the predecessor of the United Nations, the League of Nations, for the Jewish People.8

The second paragraph of the preamble of the Mandate for Palestine therefore reads:

“Whereas the Principal Allied Powers have also agreed that the Mandatory should be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 2nd, 1917, by the Government of His Britannic Majesty, and adopted by the said Powers, in favor of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, it being clearly understood that nothing should be done which might prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine … Recognition has thereby been given to the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine and to the grounds for reconstituting their national home in that country ...”9 [italics by author].

The ICJ erred in identifying the “Mandate for Palestine” as a Class “A” Mandate.

The Inernational Court of Justice also assumed that the “Mandate for Palestine” was a Class “A” mandate,10 a common, but inaccurate assertion that can be found in many dictionaries and encyclopedias, and is frequently used by the pro-Palestinian media. In paragraph 70 of the opinion, the Court erroneously states that:

“Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire. At the end of the First World War, a class [type] ‘A’ Mandate for Palestine was entrusted to Great Britain by the League of Nations, pursuant to paragraph 4 of Article 22 of the _Covenant …”11 [italics by author].

Indeed, Class “A” status was granted to a number of Arab peoples who were ready for independence in the former Ottoman Empire, and only to Arab entities.12 Palestinian Arabs were not one of these ‘Arab peoples.’ The Palestine Royal Report clarifies this point:

“(2) The Mandate [for Palestine] is of a different type from the Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon and the draft Mandate for Iraq. These latter, which were called for convenience “A” Mandates, accorded with the fourth paragraph of Article 22. Thus the Syrian Mandate provided that the government should be based on an organic law which should take into account the rights, interests and wishes of all the inhabitants, and that measures should be enacted ‘to facilitate the progressive development of Syria and the Lebanon as independent States’. The corresponding sentences of the draft Mandate for Iraq were the same. In compliance with them National Legislatures were established in due course on an elective basis. Article 1 of the Palestine Mandate, on the other hand, vests ‘full powers of legislation and of administration’, within the limits of the Mandate, in the Mandatory”13, 14 [italics by author].

The Palestine Royal Report highlights additional differences:

“Unquestionably, however, the primary purpose of the Mandate, as expressed in its preamble and its articles, is to promote the establishment of the Jewish National Home.

“(5) Articles 4, 6 and 11 provide for the recognition of a Jewish Agency ‘as a public body for the purpose of advising and co-operating with the Administration’ on matters affecting Jewish interests. No such body is envisaged for dealing with Arab interests.15

“48. But Palestine was different from the other ex-Turkish provinces. It was, indeed, unique both as the Holy Land of three world-religions and as the old historic homeland of the Jews. The Arabs had lived in it for centuries, but they had long ceased to rule it, and in view of its peculiar character they could not now claim to possess it in the same way as they could claim possession of Syria or Iraq”16 [italics by author].

Identifying the “Mandate for Palestine” as Class “A” was vital to the ICJ.

There is much to be gained by attributing Class “A” status to the Mandate for Palestine. If ‘the inhabitants of Palestine’ were ready for independence under a Class “A” mandate, then the Palestinian Arabs that made up the majority of the inhabitants of Palestine in 1922 (589,177 Arabs vs. 83,790 Jews)17 could then logically claim that they were the intended beneficiaries of the Mandate for Palestine – provided one never reads the actual wording of the document:

1. The “Mandate for Palestine”18 never mentions Class “A” status at any time for Palestinian Arabs.

2. Article 2 clearly speaks of the Mandatory as being:

“responsible for placing the country under such political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home” [italics by author].

The Mandate calls for steps to encourage Jewish immigration and settlement throughout Palestine except east of the Jordan River. Historically, therefore, Palestine was an ‘anomaly’ within the Mandate system, ‘in a class of its own’ – initially referred to by the British as a “special regime.”19

Political rights were granted to Jews only.

Had the ICJ Bench examined all six pages of the Mandate for Palestine document, it would have also noted that several times the Mandate for Palestine clearly differentiates between political rights – referring to Jewish self-determination as an emerging polity – and civil and religious rights, referring to guarantees of equal personal freedoms to non-Jewish residents as individuals and within select communities. Not once are Arabs as a people mentioned in the Mandate for Palestine. At no point in the entire document is there any granting of political rights to non-Jewish entities (i.e., Arabs) because political rights to self-determination as a polity for Arabs were guaranteed in three other parallel Class “A” mandates – in Lebanon, Syria and Iraq. Again, the Bench failed to do its history homework. For instance, Article 2 of the Mandate for Palestine states explicitly that the Mandatory should:

“… be responsible for placing the country under such political, administrative and economic conditions as will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home, as laid down in the preamble, and the development of self-governing institutions, and also for safeguarding the civil and religious rights of all the inhabitants of Palestine, irrespective of race and religion” [italics by author].

Eleven times in the Mandate for Palestine the League of Nations speaks specifically of Jews and the Jewish people, calling upon Great Britain to create a nationality law “to facilitate the acquisition of Palestinian citizenship by Jews who take up their permanent residence in Palestine.”

There is not one mention of the word “Palestinians” or the phrase “Palestinian Arabs,” as it is exploited today. The “non-Jewish communities” the Mandate document speaks of were extensions (or in today’s parlance, ‘diaspora communities’) of another Arab people for whom a separate mandate had been drawn up at the same time: the Syrians that the International Court of Justice ignored in its so-called “Historical background” of the Mandate system.20

Consequently, it is not surprising that a local Arab leader, Auni Bey Abdul-Hadi, stated in his testimony in 1937 before the Peel Commission:

“There is no such country [as Palestine]! Palestine is a term the Zionists invented! There is no Palestine in the Bible. Our country was for centuries, part of Syria.”21

The term ‘Palestinian’ in its present connotation had only been invented in the 1960s to paint Jews – who had adopted the term ‘Israelis’ after the establishment of the State of Israel – as invaders now residing on Arab turf. The ICJ was unaware that written into the terms of the Mandate, Palestinian Jews had been directed to establish a “Jewish Agency for Palestine” (today, the Jewish Agency), to further Jewish settlements, or that since 1902, there had been an “Anglo-Palestine Bank,” established by the Zionist Movement (today Bank Leumi). Nor did they know that Jews had established a “Palestine Philharmonic Orchestra” in 1936 (today, the Israeli Philharmonic), and an English-language newspaper called the “The Palestine Post’”in 1932 (today, The Jerusalem Post) – along with numerous other Jewish Palestinian institutions.

Consequently, the ICJ incorrectly cites the unfulfilled Mandate for Palestine and the Partition Resolution concerning Palestine as justification for the Bench’s intervention in the case. The ICJ argues that as the judicial arm of the United Nations, the International Court of Justice has jurisdiction in this case because of its responsibility as a UN institution for bringing Palestinian self-determination to fruition! In paragraph 49 of the opinion, the Bench declares:

“… the Court does not consider that the subject-matter of the General Assembly’s request can be regarded as only a bilateral matter between Israel and Palestine …[therefore] construction of the wall must be deemed to be directly of concern to the United Nations. The responsibility of the United Nations in this matter also has its origin in the Mandate and the Partition Resolution concerning Palestine.22 This responsibility has been described by the General Assembly as ‘a permanent responsibility towards the question of Palestine until the question is resolved in all its aspects in a satisfactory manner in accordance with international legitimacy’ (General Assembly resolution 57/107 of 3 December 2002.) …” the objective being “the realization of the inalienable rights of the Palestinian people” [italics by author].

To the average reader without historical knowledge of this conflict, the term “Mandate for Palestine” sounds like an Arab trusteeship, but this interpretation changes neither history nor legal facts about Israel.

Had the ICJ examined the minutes of the report of the 1947 “United Nations Special Committee on Palestine,”23 among the myriad of documents it did examine, the learned judges would have known that the Arabs categorically rejected the Mandate for Palestine. In the July 22, 1947 testimony of the President of the Council of Lebanon, Hamid Frangie, the Lebanese Minister of Foreign Affairs, speaking on behalf of all the Arab countries, declared unequivocally:

“… there is only one solution for the Palestinian problem, namely cessation of the Mandate [for the Jews]” and both the Balfour Declaration and the Mandate are “null and valueless.” All of Palestine, he claimed, “is in fact an integral part of this Arab world, which is organized into sovereign States (with no mention of an Arab Palestinian State) bound together by the political and economic pact of 22 March 1945”24 [E.H., the Arab League].

Frangie warned of more bloodshed:

“The Governments of the Arab States will not under any circumstances agree to permit the establishment of Zionism as an autonomous State on Arab territory” and that Arab countries “wish to state that they feel certain that the partition of Palestine and the creation of a Jewish State would result only in bloodshed and unrest throughout the entire Middle East”25 [italics by author].

This is not the only document that would have instructed the judges that the Mandate for Palestine was not for Arab Palestinians. Article 2026 of the PLO Charter, adopted by the Palestine National Council in July 1968 and never legally revised,27 and proudly posted on the Palestinian delegation’s UN website, states:

“The Balfour Declaration, the Mandate for Palestine, and everything that has been based upon them, are deemed null and void.”28

The PLO Charter adds that Jews do not meet the criteria of a nationality and therefore do not deserve statehood at all, clarifying this statement in Article 21 of the Palestinian Charter, that Palestinians,

“… reject all solutions which are substitutes for the total liberation of Palestine.”

It is difficult to ignore yet another instance of historical fantasy, where the ICJ also quotes extensively from Article 13 of the Mandate for Palestine with respect to Jerusalem’s Holy Places and access to them as one of the foundations for Palestinian rights allegedly violated by the security barrier. The ICJ states in paragraph 129 of the Opinion:

“In addition to the general guarantees of freedom of movement under Article 12 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, account must also be taken of specific guarantees of access to the Christian, Jewish and Islamic Holy Places. The status of the Christian Holy Places in the Ottoman Empire dates far back in time, the latest provisions relating thereto having been incorporated into Article 62 of the Treaty of Berlin of 13 July 1878. The Mandate for Palestine given to the British Government on 24 July 1922 included an Article 13, under which:

“All responsibility in connection with the Holy Places and religious buildings or sites in Palestine, including that of preserving existing rights and of securing free access to the Holy Places, religious buildings and sites and the free exercise of worship, while ensuring the requirements of public order and decorum, is assumed by the Mandatory…” Article 13 further stated: “nothing in this mandate shall be construed as conferring … authority to interfere with the fabric or the management of purely Moslem sacred shrines, the immunities of which are guaranteed.”29

In fact, the 187-word quote is longer than the ICJ’s entire treatment of nearly three decades of British Mandate, which is summed up in one sentence, and is part of the ICJ rewriting of history:

“In 1947 the United Kingdom announced its intention to complete evacuation of the mandated territory by 1 August 1948, subsequently advancing that date to 15 May 1948.”30

The Preamble of the Mandate for Palestine, as well as the other 28 articles of this legal document, including eight articles which specifically refer to the Jewish nature of the Mandate and discuss where Jews are legally permitted to settle and where they are not, appear nowhere in the Court’s document.31

Origin of the “Mandate for Palestine” the ICJ overlooked.

The Mandate for Palestine was conferred on April 24 1920, at the San Remo Conference, and the terms of the Mandate were further delineated on August 10 1920, in the Treaty of Sevres.

The Treaty of Sevres, known also as the Peace Treaty, was settled following World War I at Sevres (France), between the Ottoman Empire (Turkey), and the Principal Allied Powers.

Turkey relinquished its sovereignty over Mesopotamia (Iraq) and Palestine, which became British mandates, and Syria (Lebanon included), which became a French mandate.

The Treaty of Sevres was not ratified by all Turks, and a new treaty was renegotiated and signed on July 24 1923. It became known as the Treaty of Lausanne.

The Treaty of Sevres in Section VII, Articles 94 and 95, states clearly in each case who are the inhabitants referred to in paragraph 4 of Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations.32

Article 94 distinctly indicates that Paragraph 4 of Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations applies to the Arab inhabitants living within the areas covered by the Mandates for Syria and Mesopotamia. The Article reads:

“The High Contracting Parties agree that Syria and Mesopotamia shall, in accordance with the fourth paragraph of Article 22.

Part I (Covenant of the League of Nations), be provisionally recognised as independent States subject to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by a Mandatory until such time as they are able to stand alone …” [italics by author].

Article 95 of the Treaty of Sevres, however, makes it clear that paragraph 4 of Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations was not to be applied to the Arab inhabitants living within the area to be delineated by the Mandate for Palestine, but only to the Jews. The Article reads:

“The High Contracting Parties agree to entrust, by application of the provisions of Article 22, the administration of Palestine, within such boundaries as may be determined by the Principal Allied Powers, to a Mandatory to be selected by the said Powers. The Mandatory will be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 2, 1917, by the British Government, and adopted by the other Allied Powers, in favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country …”

Historically, therefore, Palestine was an ‘anomaly’ within the Mandate system, ‘in a class of its own’ – initially referred to by the British Government as a “special regime.”

Articles 94 and 95 of the Treaty of Sevres, which the ICJ never discussed, completely undermines the ICJ’s argument that the Mandate for Palestine was a Class “A” Mandate. This erroneous claim renders the Court’s subsequent assertions baseless.

The ICJ attempts to overcome historical facts.

In paragraph 162 of the Advisory Opinion, the Court states:

“Since 1947, the year when General Assembly resolution 181 (II) was adopted and the Mandate for Palestine was terminated, there has been a succession of armed conflicts, acts of indiscriminate violence and repressive measures on the former mandated territory” [italics by author].

The Court attempts to ‘overcome’ historical legal facts by making the reader believe that adoption of Resolution 181 by the General Assembly in 1947 has present-day legal standing.33

The Court also seems to be confused when it states in paragraph 162 of the opinion that “the Mandate for Palestine was terminated” – with no substantiation [E.H., Unless the Court has confused the termination of the British Mandate over the territory of Palestine with the Mandate for Palestine document] as to how this could take place, since the Mandates of the League of Nations have a special status in international law and are considered to be “sacred trusts.” A trust – as in Article 80 of the UN Charter – does not end because the trustee fades away. The Mandate for Palestine, an international accord that was never amended, survived the British withdrawal in 1948 and is a binding legal instrument, valid to this day (See Chapter 9: “Territories – Legality of Jewish Settlement”).

The Court affirmation of the present validity of the Mandate for Palestine is evident in paragraph 49 of the Opinion:

“… It is the Court’s view that the construction of the wall must be deemed to be directly of concern to the United Nations. The responsibility of the United Nations in this matter also has its origin in the Mandate [for Palestine] …”

Addressing the Arab claim that Palestine was part of the territories promised to the Arabs in 1915 by Sir Henry McMahon, the British Government stated:

“We think it sufficient for the purposes of this Report to state that the British Government have never accepted the Arab case. When it was first formally presented by the Arab Delegation in London in 1922, the Secretary of State for the Colonies (Mr. Churchill) replied as follows:

“That letter [Sir H. McMahon’s letter of the 24 October 1915] is quoted as conveying the promise to the Sherif of Mecca to recognize and support the independence of the Arabs within the territories proposed by him. But this promise was given subject to a reservation made in the same letter, which excluded from its scope, among other territories, the portions of Syria lying to the west of the district of Damascus. This reservation has always been regarded by His Majesty’s Government as covering the vilayet of Beirut and the independent Sanjak of Jerusalem. The whole of Palestine west of the Jordan was thus excluded from Sir H. McMahon’s pledge.

“It was in the highest degree unfortunate that, in the exigencies of war, the British Government was unable to make their intention clear to the Sherif. Palestine, it will have been noticed, was not expressly mentioned in Sir Henry McMahon’s letter of the 24th October, 1915. Nor was any later reference made to it. In the further correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon and the Sherif the only areas relevant to the present discussion which were mentioned were the Vilayets of Aleppo and Beirut. The Sherif asserted that these Vilayets were purely Arab; and, when Sir Henry McMahon pointed out that French interests were involved, he replied that, while he did not recede from his full claims in the north, he did not wish to injure the alliance between Britain and France and would not ask ‘for what we now leave to France in Beirut and its coasts’ till after the War. There was no more bargaining over boundaries. It only remained for the British Government to supply the Sherif with the monthly subsidy in gold and the rifles, ammunition and foodstuffs he required for launching and sustaining the revolt”34 [italics by author].

- See Appendix A. “Mandate for Palestine.” ↑

- See Appendix I. ICJ Advisory Opinion, 9 July 2004. ↑

- See Appendix A. “Mandate for Palestine,” first sentence: “Whereas the Principal Allied Powers have agreed, for the purpose of giving effect to the provisions of Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, to entrust to a Mandatory selected by the said Powers the administration of the territory of Palestine, which formerly belonged to the Turkish Empire, within such boundaries as may be fixed by them.” [italics by author] ↑

- For more on this subject see, Popular Searches: Territories and Palestinians at http://www.MEfacts.com/. ↑

- Palestine is a word coined by the Romans around 135 C.E. from the name of a seagoing Aegean people who settled on the coast of Canaan in antiquity – the Philistines. The name was chosen to replace Judea, as a sign that Jewish sovereignty had been eradicated after the Jewish Revolt against Rome. In the course of time, the name Philistia in Latin was further bastardized into Palistina or Palestine. In modern times the name ‘Palestine’ or ‘Palestinian’ was applied as an adjective to all inhabitants of the geographical area between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River – Palestinian Jews and Palestinian Arabs alike. In fact, up until the 1960s, most Arabs in Palestine preferred to identify themselves merely as part of the great Arab nation or as part of Arab Syria.

Until recently, no Arab nation or group recognized or claimed the existence of an independent Palestinian nationality or ethnicity. Arabs who happened to live in Palestine denied that they had a unique Palestinian identity. The First Congress of Muslim-Christian Associations (Jerusalem, February 1919) met to select Palestinian Arab representatives for the Paris Peace Conference. They adopted the following resolution: “We consider Palestine as part of Arab Syria, as it has never been separated from it at any time. We are connected with it by national, religious, linguistic, natural, economic and geographical bonds.” See Yehoshua Porath, “The Palestinian Arab National Movement: From Riots to Rebellion,” Frank Cass and Co., Ltd, London, 1977, vol. 2, pp. 81-82.↑ - See Appendix F. Article 22 of The Covenant of The League of Nations, A/297, April 30 1947. ↑

- Palestine Royal Report, July 1937, Chapter II, p. 38. ↑

- See: Appendix A. “Mandate for Palestine.” ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- The British Government used the term ‘Special Regime.’ ↑

- See Appendix I. ICJ Advisory Opinion, 9 July 2004. ↑

- Class “A” mandates assigned to Britain was Iraq, and assigned to France was Syria and Lebanon. Examples of other type of Mandates were the Class “B” mandate assigned to Belgium administrating Ruanda-Urundi, and the Class “C” mandate assigned to South Africa administering South West Africa. ↑

- The “Palestine Royal Report”, July 1937, Chapter II, p.38 ↑

- Claims that Palestinian self-determination was granted under Chapter 22 of the UN Charter and the ‘pre-existence’ of an Arab governmental structure (of a host of fallacies) can be found in Issa Nakhlah, “Encyclopedia of the Palestinian Problem” at http://www.palestine-encyclopedia.com/EPP/Chapter01.htm. (11452) ↑

- Palestine Royal Report, July 1937, Chapter II, p. 39. ↑

- Ibid. p. 40. ↑

- Citing by the UN. 1922 Census. See at: http://www.unu.edu/unupress/unupbooks/80859e/80859E05.htm. (11373) ↑

- See: Appendix A. “Mandate for Palestine.” ↑

- Palestine Royal Report, July 1937, Chapter II, p. 28, paragraph 29. ↑

- The League of Nations puts Syria under French mandate. Syria gained full independence on 17 April 1946. ↑

- For this and a host of other quotes from Arab spokespersons on the Syrian identity of local Arabs, see http://www.yahoodi.com/peace/palestinians.html. (11538) ↑

- See Appendix I. ICJ Advisory Opinion, 9 July 2004, paragraphs 70-71. ↑

- See doc. at: http://www.mefacts.com/cache/html/un-documents/11188.htm. (11188) ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- Ibid. ↑

- See Appendix G. Article 20 of the PLO Charter. (10366) ↑

- The Palestinians pretend that all anti-Israel clauses were abolished in a three day meeting of the Palestinian National Council (PNC) in Gaza in April 1996. In fact, the Council took only a bureaucratic decision to establish a committee to discuss abolishment of the clauses that call for the destruction of Israel as they had promised to do at the outset of the Oslo Accords, and no further action has been taken by this ‘committee’ to this day. ↑

- See Permanent Missions to the UN, at: http://www.palestine-un.org/plo/pna_three.html. (11361) ↑

- See Appendix I. ICJ Advisory Opinion, 9 July 2004. ↑

- Ibid. Paragraph 71. ↑

- See: Appendix A. Article 2 of the “Mandate for Palestine.” ↑

- See Appendix F. Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations. ↑

- See Chapter 4, Resolution 181, The “Partition Plan”. ↑

- The “Palestine Royal Report,” July 1937, Chapter II, p. 20. ↑